STRONG TEAMS DON’T HAPPEN BY CHANCE

The Science of Supportive Workplaces

w/ Dr. Jessica Stern

Use the buttons above to listen now.

Transcript - The Science of Supportive Workplaces

Rich Rininsland: On this episode of Team Building Saves the World.

Jessica Stern: One of the main reasons why people go into therapy is similar to why I think a lot of people decide to exit a workplace.

That kind of language is probably the way we’ll all be speaking in five to 10 years, which is hilarious and maybe a little depressing.

You can even make an argument to your boss, “Hey, look man, there’s this research showing that if I get this, you know, 15 minute walk in, I’ll be a better employee and I’ll be less irritable” because it’s true.

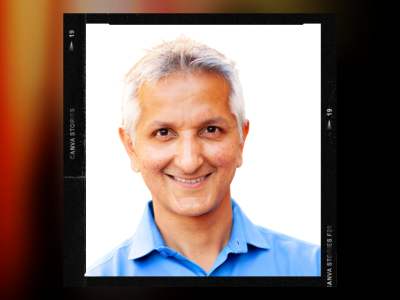

Rich Rininsland: Hello, team. It’s me. Your old friend, Rich Rininsland, host of Team Building Saves the World. And today we’re gonna take a lesson on the psychological impacts of workplace relationships and conflict resolution with psychologist, author, researcher, and assistant professor of Psychological Science at Pomona College in California, Dr. Jessica Stern.

But first I have to share some love with all of my supporters at TeamBonding. If your team is ready to experience teamwork through the. Power of Play then visit TeamBonding.com to learn more. Now, team, let’s get our science on as we talk with the co-author of Beyond Difficult, Dr. Jessica Stern.

Dr. Jessica Stern. Thank you so much for coming on the show. It’s great to have you here.

Jessica Stern: Thanks so much, Rich. Glad to be here.

Rich Rininsland: Thank you. And let’s just start off, you’re a clinician, you’re a therapist, is that correct?

Jessica Stern: My co-author Rachel Sampson, is a therapist. I, myself am a, a researcher and a psychologist.

I teach about relationships and mental health in a variety of contexts at Pomona College.

Rich Rininsland: Fabulous. And you wrote a book together, you and Rachel Sampson called Beyond Difficult, what was the impetus for this book?

Jessica Stern: So Rachel and I actually met at an unlikely location at the University of Minnesota.

So my co-author Rachel’s from Adelaide, Australia, I’m from Southern California, and we happened to be at a professional training in Minnesota one summer. And it was 10 days of intensive training about attachment theory and close relationships, kind of focused on early childhood, but really also looking into adulthood as well.

And Rachel and I hit it off immediately. We had so many shared interests and we formed a friendship back in 2018 that has lasted until today, even despite being in very different time zones and different hemispheres. And at some point Rachel actually had the idea: hey, why don’t we write a book together and try and translate everything that she knew from working with all these therapy clients and everything I knew from working in a laboratory with, you know, basically observing people and their interpersonal dynamics for about 10 years.

Why don’t we write a book that communicates this to a broader audience so more people can kind of benefit from these ideas. And so we pitched to a couple different publishers, but ultimately a firm press reached out to Rachel and said, “do you wanna write a book for adults?” And we said, “yeah.”

One of the main reasons why people go into therapy is similar to why I think a lot of people decide to exit a workplace, which is difficult relationships. So that ended up being kind of the crux of the book is, you know, how do we navigate difficult people in our lives and difficult interpersonal situations.

When our brain spends so much time ruminating about these things, and yet there’s no real guide to how to deal with them. So that was kind of the impetus for the book. And we wanted it to be really accessible so that anybody, including leaders, folks in all sorts of different sectors could pick it up and really feel like they had a handle on how relationships work.

Rich Rininsland: Fantastic.

So let’s dig in. What are some of the main reasons we find for actually having conflicts that occur at work?

Jessica Stern: Yeah, you know, in my own experience, there are kind of a few main reasons. And the first is poor communication. A lot of the times when there’s difficulty at work, it’s because either somebody didn’t communicate their expectations well, or maybe there was no conversation about what was actually expected in kind of an explicit way, or people start kind of talking past each other. And with more and more communication happening, not face-to-face, but over a text, email, slack. There’s a whole lot actually within our communication skills that kind of gets buried when you just receive a text message, especially something that could be construed as criticism. So there are communications and miscommunication issues that can be kind of at the heart of a lot of workplace difficulty.

A second reason is that. People feel insecure in their relationships, either at work or at home, and then bring that to work. So one of the things we talk about in the book is the fact that your attachment style, basically your pattern of interacting with other people is like the lens through which you perceive other people’s communication with you.

So as an example. A securely attached person has a positive view of themself. You know, ” I’m basically a competent person” and views other people positively as well, so other people are generally trustworthy. That’s my general worldview, and if I take that into a workplace situation, what the research shows is that securely attached people tend to be better communicators.

They also tend to be more trustworthy leaders and they tend to value relationships more, which means they value teamwork a little bit more.

Rich Rininsland: Hmm.

Jessica Stern: Now, if I’m not securely attached, maybe I am avoidant and that pattern looks like, I think “I’m pretty great, but other people are the problem, other people. It’s not me, it’s you.”

Rich Rininsland: Right, right, right. I’ve had that throughout my career many, many times. Yeah.

Jessica Stern: And so for avoidant people, the central issue is trust. I don’t know that I can truly lean on other people for support when I need it, and therefore I’m gonna be really, really self-sufficient. And part of what that can look like is focusing only on a task, not delegating to other folks, not trusting other people to do their work well.

And kind of with withdrawing a little bit socially from a team or being fairly aloof or unavailable.

There’s a third pattern, also a type of insecure attachment, called anxious attachment. And these are the folks who don’t tend to rise to the level of leadership, in part because they’re very dependent.

So their view of themselves is, “I’m not very competent. I really need other people to reassure me. I’m doing okay. And I worry a lot about how am I doing?” So there’s a lot of reassurance seeking, “is this okay?”, “I sent this thing to this person and they didn’t respond. Do you think that means they’re mad at me?”

And really what these folks crave is closeness and being liked, but that can sometimes come at the expense of actual performance. And, they don’t have the confidence to really stand behind their work. So you can imagine there are these. Three types. Secure, insecure avoidant, insecure anxious, and they’re all kind of rubbing up against each other.

And sometimes that can lead to some conflict.

Rich Rininsland: And, I have to say, I personally, I have heard of the secure attachment type before, but I cannot actually remember anyone in my varied career and, you know, 50 some years of life that I could really say was that particular type.

For the most part, I have met a lot of very insecure people. You know who you are out there, and I still love you all dearly, but how hard is it to get these different, very disparate types even to start talking to each other? How do you find a common vocabulary with this need behind it?

Jessica Stern: I think the first thing is to just recognize that people have different interpersonal patterns than you might, and so they’re coming to a team or an organization with different expectations around relationships. So as a securely attached person, I expect that my team is trustworthy, that I can bring feedback to somebody and have it be received well, and those expectations may or may not be correct.

I might bring feedback, trusting that my boss is gonna take it well and be hugely surprised when they don’t. So sometimes our expectations are or are not accurate and we adjust accordingly. I think for me, the really hopeful part is there’s actually some really cool longitudinal research that follows different leaders and employees over time.

And what they show is regardless of what attachment style you ought to begin with, if you have repeated interactions with responsive and supportive leaders and with cohesive groups, you actually show improved attachment security at work over time. So if you can build a workplace culture where employees feel supported, seen, and like their voice matters.

Over time, people kind of move in the secure direction. But the opposite you can imagine is also true if there’s a workplace culture where everybody’s out for themselves. It’s a dog eat dog world, nobody is allowed to give really honest feedback. You can imagine that really eroding even the most secure employees sense of trust and psychological safety.

Rich Rininsland: Right. Exactly. Yeah. We’ve talked about psychological safety a lot of the last couple of years on the podcast and, even that secure person has still has to have that psychological safety, even though they’re bringing a lot of it for themselves, seemingly, they still need to know that there are people who have their back or like you say, even just make sure they have the skillset to be able to keep up.

So, what can we do when it starts falling apart? Or let me, let me actually rephrase. How can we recognize that that’s what’s actually causing a lot of the turmoil in the workplace, and what can we do to course correct?

Jessica Stern: That’s such a good question. I mean, I think the very first piece of this is feedback.

Building feedback into the culture so that everyone expects that there will be some moment in time over the course of year, hopefully multiple times, in a year, where people can give feedback in a way that is open, honest and not going to blow back in their face.

My, my dad, who is always an inspiration to me ,passed away a few years ago, but he was an organizational psychologist for 30 years. And he specialized in leadership development. And so these corporations would call him in and say, you know, “Hey Dennis, we’re having a problem where our management just doesn’t know how to deal with this particular team. Can you come in and help?” And part of what he would do first is just a 360 survey of everybody who worked with a particular manager.

And he would kind of meet with them individually, type up his notes, and then he would be the person to actually deliver the feedback to the manager in a way that masked people’s identities. And part of his skillset was he was interpersonally just a really easygoing person, and he was very good at putting these managers at ease and presenting the feedback in a way where they wouldn’t be immediately defensive.

But I think for anybody, you know, it has to start with feedback. And oftentimes the feedback that is not being given is the feedback from the ground up or from the employees to the leadership. There’s usually plenty of top down feedback.

So oftentimes the employees pretty much know where they are or are not doing well, that’s not always the case, but feedback in order to be effective, the research shows that feedback has to be mutual. It has to be a two-way street. So if there can be systems set up such that at regular intervals, people can check in and say, here’s what’s working for me as an employee, and here’s what’s not.

And they can do it in such a way where they don’t feel at risk of losing their job.

Rich Rininsland: Yeah.

Jessica Stern: That’s a first step to figuring out what is wrong, what’s at the core of this issue. So I think that’s kind of a first place to start. And then secondly, you know, the more that people can kind of take in the feedback and not just say, “I hear you”, but then implement it. So that’s sometimes the piece that’s missing. And in the book, we actually interview a woman who was dealing with a difficult supervisor. And in the moment during their meetings, the supervisor seemed to take to heart her feedback. And say, “I hear you. I hear this is not working for you. Let’s work on it.” And yet in every subsequent interaction, she kept doing the same thing that they had tried to talk through. So unless the feedback is implemented, nothing is going to change.

Rich Rininsland: For the length of this podcast, for the amount of time that I have been on, there has always been a very strong feeling of it’s manager’s responsibility to actually make this function, to make it work. And they do bear a large brunt of it, but of course they also have their managers that they have to talk to all the way up to the C-suites. What can the individual employee do to make sure that if they’re not being heard, not being heard correctly, that they start to be heard correctly and to make sure that they’re still hearing everybody on their level correctly as well.

Jessica Stern: That’s a really good point. It always takes two to tango. So in any relationship, each person is bringing their own stuff, which can be positive or negative. And there are definitely things that an individual employee can do, and one of them is just being honest about their needs.

So in the book we talk about how, and this is true in workplaces too, neurodiversity. So somebody whose brain works a little bit differently from other people’s, this could be somebody with ADHD or right, somebody with autism spectrum disorder, they might appear outwardly to their supervisor to be a difficult employee when actually what they need is: “I need a quiet workspace because I get open overstimulated in an open plan environment, and that makes me irritable and then I don’t react well to other people”.

This is such a common thing, especially for folks on the autism spectrum. If you can be honest as an employee, “Hey, I know that my productivity has been suffering, I know that I didn’t come across well in that meeting. First, I take accountability, and I think one of the reasons is this office environment is a little overstimulating for me. And the way that I work best would be if I could have my own space, at least for a couple hours a day. Is there any way that we could test that out and maybe see if things improve and you know, I’m willing to be flexible, but I’d love to try this out because I think this is what I need to do better.”

And you know that that’s stating a need that you’ve recognized within yourself. And then, your boss can say yes or no, but at least you’ve said, here’s what I think I need to do better in the future. That’s one thing.

Rich Rininsland: Right. Right. Plus it could be, you’re talking about even generationally at work.

Because we’re now looking at six generations in the workplace. I mean, they don’t speak the same language, usually one with the other, so it may not be a psychological issue or a biochemical issue. It could simply be: “I’m fresh out of college and I have all of these great ideas. Meanwhile, the guy I am sitting next to is approaching retirement age and he thinks he knows how everything works best already.”

Jessica Stern: Absolutely. Yeah, the generational piece is is an interesting one. So I work with a lot of gen Z students and I supervise a small team of student researchers in my lab where we study relationships.

And that has been an interesting challenge and one that’s often fun. But, always a bit of a challenge to navigate.

Rich Rininsland: How do you handle that though? I mean, what’s the fun? Because I think the people out there who are thinking of it going, “wait, there’s a way to do this, that’s fun? How do I handle that?”

Jessica Stern: I think what I find fun is making time to be curious about their experience. And, hopefully, the younger generation can do the same for the older generations, so it’s a two-way street. But I think if we can be genuinely curious about what perspectives, what unique perspectives is this generation bringing, and for older generations it’s crap ton of experience that the younger generation does not act.

And for the younger generation. You know, they’re bringing all of this media savvy in part that the older generation might not have. And a real finger on the pulse of where the culture is going in the next five, 10 years. There’s really cool research, just as an aside, that adolescent girls tend to be at the forefront of the way that language changes over time .

So if you listen to teen girls talk, that kind of language is probably the way we’ll all be speaking in five to 10 years, which is hilarious and maybe a little depressing.

Rich Rininsland: Yeah. I have a teenage daughter and that terrifies me.

But I get it. I do see it.

Jessica Stern: They’re driving the communication patterns.

Rich Rininsland: Yeah. That’s incredible. Oh, I’m never gonna let her listen to this episode. Okay.

Jessica Stern: Keep it under wraps.

Rich Rininsland: Right. But it sounds to me that we’re getting back to, and I don’t wanna call it a buzzword, but kind of a buzzword that has been coming up a lot in recent conversations I’ve been having about empathy.

So as a researcher yourself how would you define empathy and what kind of role does it have in this kind of interpersonal communication that you specialize in?

Jessica Stern: Empathy is often misinterpreted. This softness, this kind of touchy feely, I’m a doormat kind of thing. I think of empathy as tremendously powerful and one of the coolest skills we have as human beings.

Although actually some of our closest primate relatives are capable of empathy too. So chimps and bonobos seem to also have what you might call empathy. But in humanities…

Rich Rininsland: Looking at the world today, they’re probably slightly better.

Jessica Stern: Exactly. Exactly. So empathy can be thought of in two categories.

Emotional empathy is really about resonating with somebody else’s experience. And I’m feeling to some degree what you’re feeling. But not so much that I get distressed by it.

So there’s a difference between resonating with “Oh yeah, I feel your sadness right now.” Versus me starting to cry when you’re upset. Because that’s not really useful to anybody. And what the data show is that emotional empathy is really effective in doing two things, reduces aggression. So you can imagine in a workplace, if I’m empathizing with somebody’s distress, I’m much less likely to bully them, Criticize, be negative toward them in a vulnerable moment.

But it also can motivate pro-social behavior. So if I see you’re struggling with something and I feel or resonate with your emotions, I’m much more likely to do something about it.

So you can imagine that would be really important for things like team building where I can recognize that my team member is not doing well.

We can move forward, something needs to be addressed. So that’s the emotional side, the cognitive side. So cognitive empathy is really about perspective taking. Can I step into your shoes? See from your point of view, and maybe even consider points of view that might differ from mine. And this is really important for creativity.

Coming up with new ideas and just being open to innovation. So if I’m able to take diverse perspectives and put myself in this person’s shoes and that person’s shoes, A, I’m better at resolving conflict when it comes up because I can kind of see where people are coming from. But B, it allows for more creativity because I’m not so stuck in one way of seeing the world.

So I think empathy, can be a superpower, and it doesn’t have to be all soft and squishy. It can really be about insight into other people’s minds. And it’s a muscle we can build. So it’s not a static skill. It’s something that with practice and intention, we can refine over time. We actually, in the book, we talk about some ways of doing that.

Rich Rininsland: Gimme some please. Because that always seems to be the hardest thing for guests to answer. How can you take someone who may not be naturally empathic, whether emotionally or cognitively, but can build it up into themselves?

Jessica Stern: The first thing is just to be curious. So if you find yourself, especially with a difficult person or somebody you don’t like at work. You know, ask them about themselves. Get the conversation away from whatever the point of tension is, just for a moment and try to see, you know, what, what is this person like? What makes them tick? What brought them to this company in the first place? What’s their experience like?

Just be curious about it. And then. You’ll know more about their perspective because you’ve asked them.

So it’s not always just that you have to magically guess or be clairvoyant about what’s in somebody else’s mind. You can ask them, you know? It’s not it’s not rocket science. So that’s the first thing is just to be curious.

The second thing is in your free time. Pick up a work of fiction because there’s really cool data showing that reading fiction enhances cognitive empathy because you’re putting yourself in the shoes of a character. Or you could even read memoir, you know, if you wanted to read about the memoir of somebody in your field who you really look up to, that’s fine too.

But the idea is your brain is practicing projecting yourself into another person’s world.

Rich Rininsland: Awesome.

Jessica Stern: And. You’re basically building a muscle by doing something that is enjoyable and pleasurable. So I really like that one in particular.

Rich Rininsland: Very, very nice. But what about when we get to the point where it’s all falling apart?

The conflicts are coming fast and furious and something has to give whether negatively or positively. Can you at least gimme a story if you can, about a moment that was so explosive and we had to resolve it. We had to, you know, get rid of the angry feelings or the difficult sensations that we’re having towards each other and make sure we can all still function in the same space.

Jessica Stern: Yeah. Well, so in the book we interview a woman named Tan V, and she’s working in a hospital setting. She’s managing a new employee. And they seem to be on the same page for the first couple weeks, and then she just notices that there’s something wrong in their relationship. There’s more and more tension. There are more of these little tiffs that keep on recurring that don’t seem to match her view of things. But meanwhile, this employee is kind of withdrawing and behaving more and more passive aggressively.

And so what Tan V decides to do is have a one-on-one with her. And say, “look, I wanna be a better supervisor to you, and it’s clear that something’s not working, but I don’t know what it is. Can you help me understand what it is?”, and unfortunately, this really backfires. So she’s doing the right thing. She’s asking for feedback. She’s creating a safe environment for her employee to do that. What ends up happening is she gets the kitchen sink. Here’s everything from the past five months of working with you that has really ticked me off, in list form. It was just kind of an explosive interaction.

And Tan V’s response was just to take it in and just say, “thank you for your feedback”. But then she goes home and you know, she’s totally undone by this. ” How am I supposed to work with this person who thinks I’m terrible?”

So she does a few things. The first thing she does is: she talks to somebody at work, an administrative manager in private, you know, confidentially. And she trusts this woman and she says: ” here’s what happened. I’m feeling really distressed about this”.

So first of all, this woman listens to her, provides some support and says, “I think there needs to be some follow up to this conversation. It sounds like you weren’t able to express your side of the story”.

So then she goes home, she vents to her husband. So first of all, she gets all of that energy out. Otherwise we just take it right back to work and do the same thing that this person has just done to us. So she’s able to process in private with her husband and she decides to invite some friends over and she’s saying, “this thing is kind of weighing on my mind. Do you have advice?”

So what I love about this story is she’s getting support from about five different places. She’s not just relying on, “oh, okay, I need to take this on by myself and resolve this explosive interaction”. She’s seeking support from somebody at work who kind of knows the workplace culture. She’s processing with her husband, who has no stake in the game particularly, and is just willing to listen to her vent.

And she’s saying, “okay, people who I know and trust, what would you do in this situation?” And based on all of those supports, she feels less reactive. So when she goes into the next interaction with the employee, she’s not so full of rage that suddenly things escalate further. And the second thing she does is from talking to all these people, she says, “okay, I think that I need to actually write down what I wanna say and practice it once before going into this meeting because I know it’s gonna be fraught”.

So then she comes and says. “Hey, we had, you know, we had this conversation. I know it ended in a way we didn’t, neither of us liked. Here’s what I think is happening and what can we do, ( very solutions oriented), what can we do to work better together in the future?” So she gave some feedback to the employee, first of all, so that it was a two-way street, and so that that employee could take some accountability for how the dynamic was playing out. So it wasn’t just on Tan V to take all the blame and just sort of say, “okay, thank you”. But she was able to present her side of things and because she framed things as solutions oriented, “Hey, let’s work toward this goal together”, rather than, “here’s everything wrong with you as a person”.

They were able to kind of shift away from making it all personal and making it so explosive and, “oh, we actually have a shared goal and here’s the point by point plan for how we’re gonna pursue it”. So A, their roles were much clearer from that conversation. And B, now they were in an allyship rather than antagonistic.

So, part of that was, she needed to ask for feedback. The feedback went terribly, but at least she knew it was under the surface. And then was able to work with that tension and kind of re-channel the energy toward here’s the goal we actually wanna pursue.

Rich Rininsland: Excellent. That’s really excellent because I have heard, and as I was saying earlier, that there’s so many people for whom the manager is always the catalyst, whether it’s the blame for things going poorly or you know, they have to be the ones to make things right. I’m glad that that was a more positive interaction for somebody. That’s really grand.

Jessica Stern: Yeah.

Rich Rininsland: Because I have heard so many stories the other way around.

What about those people who maybe don’t have such a strong support system outside of the office?

You know, there might be those people who are still single or maybe their friends, you know, they were hoping their friend base would come from work itself, or maybe their friend base is solely around work itself. What can those people do to help get themselves straight before going back into the situation?

Jessica Stern: A lot of the escalation that we see in conflict and negative interactions comes from not being able to handle emotion well and seeking support from other people is one way that humans can manage emotion. So if you do have a support network at work, use it to the extent that you feel it’s appropriate to.

If you have a trusted coworker who you know is not gonna spill the beans on whatever you’re telling them, you know, reach out to them. “Hey, can I take you to lunch? There’s this thing with my supervisor, I’d love to talk it through with you”. So it’s totally fine to lean on people at work if you feel you can trust them.

And if you’re new in a workplace, you know, you could take a chance and show maybe a little bit of vulnerability and just see how that’s responded to before going hog wild. So intimacy is built over time, in any relationship. So take advantage of those social supports. But there are other ways that we can manage emotion too.

And you know, let’s say you don’t have the best support network, A, you can build one. So there’s always a possibility of strengthening the bonds that you do have. There might have been somebody who’s kind of an acquaintance, but you get a good read on them and you feel really seen and safe talking to them, even if it’s in a brief interaction.

See if they wanna grab coffee or you know, do something on a weekend, go for a walk. So you can always build those support networks if you don’t have them. That’s number one. Number two, one of the greatest ways to manage strong emotion is exercise and, I am in no way athletic myself. But, I’ve been in plenty of conflict scenarios where I felt so much better and more competent after walking around the block.

So even, even if you only have five minutes to walk around the office and then come back and meet with this terrible person that you have to deal with, do it. Because what we know is that your physiology really impacts your brain.

And this is a, just a cool little sidebar, but there was recently a meta-analysis of all the different exercise modalities that have been used to treat depression, and they looked at jogging yoga, and then they compared all of these things to using drugs and getting therapy. Turns out the number one thing that seems to have the biggest impact on depression is dance. It was even more effective than using SSRIs, so drugs and therapy.

But, we also know from research on couples that taking a 20 minute break and often doing something physical can really lower the temperature on a conflict. And that, could mean you go for a run, that could mean that you dance it out, but whatever it is, you know, move your body if you wanna move out of feeling stuck in a negative dynamic.

Rich Rininsland: Is there a way to do that at work that isn’t a mandatory 11:30 dance break before going to lunch? Which by the way, anybody out there who starts doing that, please let me know if it functions.

Jessica Stern: Well if you’re an early riser, which I am not, doing some sort of cardiovascular exercise as part of your morning routine can be great.

But if, if that’s not you, building in a little bit of movement during your lunch break will probably improve mood and productivity for the rest of your day. So you can even make an argument to your boss, “Hey, look man, there’s this research showing that if I get this, 15 minute walk-in, I’ll be a better employee and I’ll be less irritable” because it’s true.

Rich Rininsland: Yeah. Yeah. And speaking of those managers, what can they do? I mean, we’ve discussed some of the giving that employee the open space to actually to be themselves, to speak freely, but what else can happen so that they have created or continue to create? Because I have heard of so many managers who think, I have this. We are good. Everybody’s functioning, the flow is happening, the work is getting done, and everybody seems to be happy, and then suddenly it just all goes wrong.

So what can they do for themselves primarily just to make sure that they’re in the reality of the moment?

Jessica Stern: So I think the best strategy is building that culture of feedback at regular intervals. So I’ll just give one example, when I was in graduate school, many people might think that being in academia is not being in the real world, but the kinds of dynamics that happen at work and in a large corporation absolutely happen in academia.

We work for a big university. There are leadership changes all the time. We get funding pulled. There are tensions around group dynamics and who’s getting credit for stuff. And we have supervisors who train us and have a lot of control over the future of our career. So I think this is relevant for a variety of reasons.

My supervisor in graduate school had a twice a year feedback session with every one of her students who was on this research team. And they followed a set structure. So we always knew ahead of time what we were being evaluated on and what the kinds of expectations for that meeting were. And the first time I went into one of these, I was terrified.

I thought, “oh, she’s just going to, lay it on me about all the things I haven’t gotten done”. But by the end of the meeting. The way, part of the way it was structured was that I, as the supervisee, would always speak first. Which was sort of interesting. And what she asked me to do was, first a self-evaluation.

What is going well for you? What’s not going well for you? How do you think you’ve done? How do you think your progress is going? What additional supports do you need? And how are things going with the rest of the team from your point of view? So it started with the person with less power speaking first.

And, I got time ahead of time to write down my thoughts and really reflect on, “yeah, how am I doing and what are the things I need to work on?” And then secondly, ” how was she doing as a supervisor?” So the other thing that I got room to say was, “here’s what’s working for me really well in our relationship. Here’s something that’s not really working for me. Can we change it in some way?” So that was my part. And then she would kind of do the same thing with me: ” here are the things that I see are going well. Here are some of the things that I don’t think are going well”, and we could kind of see where we were lined up, where we have the same narrative and where maybe we were worlds apart. And I think because that first meeting went well, I left so energized, like, “oh, I know exactly what I need to work on”. And she had given me the names of three people in our department to reach out to for help. So, “oh, I need to get better at this skillset. I need to get better at analyzing data. Here’s the person to go talk to and meet with to improve”, so she, she didn’t just say, “oh, you need to improve on this”. She told me how to get there.

Rich Rininsland: Right. Fantastic. Yeah.

Jessica Stern: Yeah. And because this was built in twice a year, I always knew to expect it and I think because of that I worked better.

So that’s part of it, is having that culture so that there are regular check-in so that you’re not blindsided by, “here’s this thing that’s actually going really, really terribly”, but actually you kind of know ahead of time. Because you’ve said, “here’s what I think is going on”. And your employee can say ” that’s my perception”, or “No, you’re way off base”.

Rich Rininsland: That’s fantastic.

Dr. Stern. Can I just say thank you so much for coming on the show today. This was a wonderful, wonderful conversation. I enjoyed you being here immensely. My team out there, please give a huge round of applause for Dr. Jessica Stern, everybody!

See, they’re like employees to me. They’re just a handful of people I keep trapped under my desk just to applaud. That’s their only job.

Jessica Stern: That’s a good gig.

Rich Rininsland: And we will be having a meeting now that I know. Just to see how they’re doing, what’s life under the desk like for them. We’ll make sure it’s all excellent, nice and clear.

Excellent. Did you have a good time?

Jessica Stern: I did. Thank you. I hope you did too.

Rich Rininsland: Very much so. Very, very much so. I hope you continue to have a good time because as I warned you in the advance, it’s time for the speed round.

Jessica Stern: Okay.

Rich Rininsland: Little bit of goofy radio play there. So Dr. Stern, all this really is, is for the next 60 seconds, I’m gonna be playing some music. While I play the music. I’m gonna be asking you a series of very silly questions just to see if we can learn a little bit more about you personally. But this part of the show was started as a fun little game between facilitators.

So if you are feeling it all competitive. We have gotten to 17 questions asked within 60 seconds, so don’t feel like you have to, but if you want to, it’s fun. Alright, so I’m gonna start the music. As soon as you hear it, I’m gonna ask the first question and away we go. What’s your name?

Jessica Stern: Jessica.

Rich Rininsland: Do you have any kids?

Jessica Stern: One on the way.

Rich Rininsland: Oh, congratulations.

Do you have any pets?

Jessica Stern: Thank you. No. No, but I grew up with two dogs.

Rich Rininsland: Okay. And what job would you be terrible at?

Jessica Stern: Computer scientist.

Rich Rininsland: How do you unwind after a busy or stressful day?

Jessica Stern: Walking with my husband in a beautiful, natural area.

Rich Rininsland: Nice.

What was your first job ever?

Jessica Stern: A research consultant for National Research Center doing citizen surveys.

Rich Rininsland: Wow. That was just a long answer unto itself. Go-to karaoke song.

Jessica Stern: Oh gosh. I will always love you.

Rich Rininsland: Pancakes or waffles?

Jessica Stern: Pancakes.

Rich Rininsland: If you could be anywhere in the world, where would you like to be?

Jessica Stern: Lima, Peru.

Rich Rininsland: What’s the most unusual job you’ve ever had?

Jessica Stern: Worked at Ben and Jerry’s scooping ice cream.

Rich Rininsland: 14. Jessica 14. Congratulations. Well done. Better than average, I’ll say especially of late, better than average.

Jessica Stern: I need to get better about my karaoke go-to.

Rich Rininsland: And I love that that’s in there because that is a great karaoke song. I don’t think people give it… whether you’re doing it, Dolly Parton or Willie Nelson or what have you. It’s just so, so good. Everybody. I highly recommend it.

Speaking of recommend Dr. Stern, where can we find your book?

Jessica Stern: You can find Beyond Difficult, if you’re, if you’ve got any listeners in Australia, they can find it on bookshelves throughout Australia and New Zealand. But if you’re in the US like I am, you can find the ebook on Amazon. There’s an audio book on Audible. And you can order a paperback copy from Readings Books.

Rich Rininsland: Jessica Stern. Thank you very much.

Jessica Stern: Thank you, Rich. Great to see you.

September 9, 2025

In this insightful TeamBonding Podcast episode with Dr. Jessica Stern, learn how to turn workplace conflicts into opportunities for growth. Dr. Stern breaks down the real reasons behind workplace tensions (hint: it’s usually poor communication and different attachment styles, not just personality clashes). And explains how to build a supportive environment through practical strategies like regular feedback sessions, proactive check-ins, and empathy-building techniques. Dr. Stern shares research-backed methods for developing both emotional and cognitive empathy, plus simple tactics like using exercise breaks to manage workplace stress and building stronger professional networks. Whether you’re managing difficult team dynamics or navigating tricky office relationships yourself, this episode delivers actionable insights for cultivating a supportive work environment where everyone can succeed.

About Dr. Jessica Stern:

Dr. Jessica Stern is a developmental psychologist and assistant professor of Psychological Science at Pomona College who brings both academic expertise and real-world insight to understanding workplace dynamics. Drawing from her PhD in developmental psychology and postdoctoral research at the University of Virginia focused on empathy development, Dr. Stern has co-authored Beyond Difficult with Rachel Samson, offering evidence-based approaches for navigating challenging interpersonal relationships in professional settings. As an educator specializing in human development, relationships, and mental health, she’s dedicated to helping people build stronger connections both personally and professionally. Following in the footsteps of her father, a veteran organizational psychologist, Dr. Stern combines rigorous research with practical wisdom to show how psychological principles can transform difficult workplace situations into opportunities for growth and understanding. Her work demonstrates that with the right tools and mindset, even the most challenging professional relationships can become sources of collaboration and success.

Dr. Jessica Stern is a developmental psychologist and assistant professor of Psychological Science at Pomona College who brings both academic expertise and real-world insight to understanding workplace dynamics. Drawing from her PhD in developmental psychology and postdoctoral research at the University of Virginia focused on empathy development, Dr. Stern has co-authored Beyond Difficult with Rachel Samson, offering evidence-based approaches for navigating challenging interpersonal relationships in professional settings. As an educator specializing in human development, relationships, and mental health, she’s dedicated to helping people build stronger connections both personally and professionally. Following in the footsteps of her father, a veteran organizational psychologist, Dr. Stern combines rigorous research with practical wisdom to show how psychological principles can transform difficult workplace situations into opportunities for growth and understanding. Her work demonstrates that with the right tools and mindset, even the most challenging professional relationships can become sources of collaboration and success.

If there's a workplace culture where everybody's out for themselves, it's a dog-eat-dog world. Nobody is allowed to give really honest feedback. You can imagine that really eroding even the most secure employees' sense of trust and psychological safety.

Jessica Stern

More great podcast episodes.

Season 6 | Episode 18

That’s a Wrap!

Season 6 | Episode 17

Work-Life Integration

Season 6 | Episode 16

Laughing it Off

Season 6 | Episode 15

Corporate Volunteerism in Action

Season 6 | Episode 14

Collaborative Play at Work

Season 6 | Episode 12

The Power of Being Present

Season 6 | Episode 11

The Age Advantage

Season 6 | Episode 10

VUCA-Proof Your Leadership